This article was published on: https://www.standardsplusinnovation.eu/comoninvent

Humans have developed all manner of technology that helps to expand our senses, but for a long time, the sense of smell got the short end of the stick. A pioneering company from Delft, the Netherlands, has changed this. With a little help from their friendly neighborhood standards organization: NEN.

Simon Bootsma is the founder and CEO of Comon Invent: “the company that developed, and is marketing, the electronic nose.”

What is an electronic nose? According to Bootsma, it’s more than meets the eye. “Sure, it’s a small device equipped with sensors that are exposed to ambient air,” he admits, holding up an unassuming white object, roughly the size of a flowerpot. “But what it really is, is a device that mimics the human olfactory system, where the brain interprets whatever signals the nose happens to pick up. Only for the eNose, its brain is a central database in the cloud.”

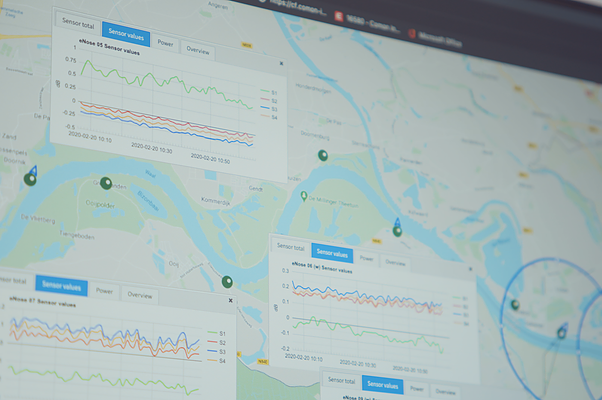

The device itself simply collects and transmits the sensor data. This means that the devices are low-cost, compact, and easy to transport all over the globe. The real innovation of the eNose, according to Bootsma, is not in the sensors: “The innovation part is not only in the hardware, but it’s more in the whole architecture behind it. The computing power in the cloud is enormous.”

Around the world, 1500 eNoses are sniffing the air in ports, oil refineries and other industrial sites. In the Port of Rotterdam alone, 250 eNoses are deployed. The combination of sensors in each nose detects changes in compounds in the air, and they send that information remotely to the cloud, where, like a fingerprint, it is matched against a whole library of chemical profiles. The scent patterns in the database are based on human references: brain associations that tell humans what they are smelling.

Hydrogen sulphide or smell of rotten eggs?

“When you smell hydrogen sulphide, you will probably think of rotten eggs, and not of some chemical you’ve never even heard of. So when a sewage tank is leaking, and concerned citizens start calling the environmental protection agencies (EPA), complaining about a foul odor of rotten eggs seeping through their windows, that’s how the system learns,” explains Bootsma. “With the eNose, we record all kinds of patterns, and we can label them with patterns that are reported by citizens. We also do a lot of big data analysis of references from human complaints, and references from the eNose recordings.”

Tracking and tracing gas emissions

The eNose is used in situations where gas emissions are likely to pose a risk of odor nuisance to the general public, who may get worried about their health or safety. If there is a gas release that can have an impact on residential areas, electronic noses can be utilized to trace the source of the emission and track the dispersion of the plume.

“In ports, there could be thousands of potential emission sources. And when there is a gas emission, you want to nip it in the bud,” says Bootsma. By placing a network of electronic noses, the actual location of gas releases and where the plume is spreading can be pinpointed. This allows the company responsible to reduce the emission, and simultaneously the EPA to inform the citizens about the cause and the expected bad smell that will pass their neighborhood.”